The defeat of Japan at the end of World War II liberated Korea, its northeast Asian neighbor, from 35 years of Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945). This included censorship of Korean language newspapers, pressure to use Japanese language and adopt Japanese names, the removal of priceless cultural artifacts to Japan, as well as acts of brutality and repression. Young Korean men were recruited as laborers and soldiers for the war effort; young women were forced to become so-called “comfort women”, in reality sex slaves for the Imperial Army. During what turned out to be the final days of the Asia-Pacific War, the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima (August 6) and Nagasaki (August 9). Japan requested a ceasefire on August 10. By the time Japan surrendered on August 15, the United States proposed (and the Soviets accepted) temporarily dividing Korea along the 38th parallel in an effort to prevent Soviet troops, who were fighting the Japanese in the north, from occupying the whole country. Japanese troops north of the line would surrender to the Soviets; those to the south would surrender to U.S. authorities.

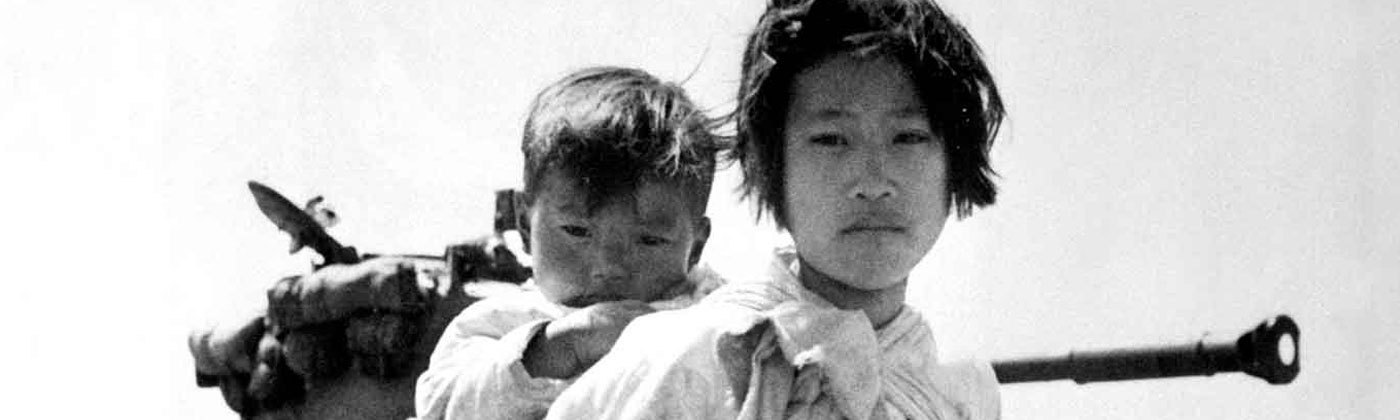

Negotiations between Washington and Moscow failed to establish a single Korean government, thereby creating two separate states in 1948: the Republic of Korea in the south and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in the north. This precipitated the Korean War (1950-53), often referred to in the United States as “the forgotten war”, when each side sought to reunite the country by force. Devastating aerial bombardment quickly reduced much of the country to rubble. More bombs were dropped on Korea from 1950 to 1953 than on all of Asia and the Pacific islands during World War II. One year into the war, Major General Emmett O’Donnell Jr. testified before the U.S. Senate, “I would say that the entire, almost the entire Korean Peninsula is just a terrible mess. Everything is destroyed. There is nothing standing worthy of the name…” Nearly 4 million people were killed, including Korean, Chinese, and U.S. soldiers, with Korean civilians becoming the largest casualty. Many more civilians were displaced, forced to flee the destruction of their homes, farms, and work places. In this chaos families became separated. When the fighting stopped many family members ended up on opposite sides of the ceasefire line. They have been separated ever since, as there has been virtually no contact between the citizens of the two states, which have maintained Cold War hostilities.

Despite enormous destruction and loss of life, neither side prevailed. In July 1953, fighting was halted when North Korea (representing the Korean People’s Army and the Chinese People’s Volunteers) and the United States (representing the United Nations Command) signed the Korean War Armistice Agreement at Panmunjom, near the 38th parallel. This temporary cease-fire stipulated the need for a political settlement among all parties to the war (Article 4 Paragraph 60). It established the Demilitarized Zone, two- and-a- half miles wide and still heavily mined, as the new border between the two sides. It urged the governments to convene a political conference within three months, in order to reach a formal peace settlement. Over 60 years later, no peace treaty has been agreed, with the continuing fear that fighting could resume at any time. Indeed, the armistice has been violated by both sides, most egregiously by the introduction of atomic weapons into South Korea by the United States in 1958, violating Article 2 Paragraph 13d of the armistice which stipulated that no new weapons be introduced into the peninsula.

Current tensions and military buildup, including North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, have grown out of this unresolved situation, with two heavily armed states on each side of the DMZ, often described as the most militarized border in the world. Both North and South Korea deploy substantial armies, maintain military bases, and conduct ongoing maneuvers as part of their readiness for the possibility of war. In addition, 28,000 U.S. troops are stationed in South Korea, a close U.S. ally to this day. The United States maintains major bases such as Osan Air Base, and Army bases: Camp Humphreys and Camp Casey, as well as conducting regular joint training with the South Korean military. The U.S. military would have operational control over South Korean forces in time of war, while South Korea is a significant importer of U.S. arms. In 2006, the United States and South Korea agreed to change the role of U.S. Forces in Korea from a defensive posture against North Korea towards a “more flexible, mobile, and rapidly deployable force” for the wider Asia-Pacific region. The United States points to the military standoff with North Korea as justification for its continued presence on the Korean peninsula. This, in turn, serves to bolster military hawks in North Korea, which continues to develop its nuclear capabilities. Moreover, the unresolved Korean conflict gives all governments in the region justification to further militarize and prepare for war, depriving their own people of resources for education, healthcare, social services, environmental protection, and coping with climate change. In addition to military policies, the United States has imposed a complex system of restrictions (original here) on trade, finance, and investment in relation to North Korea since 1950. Over the years, such sanctions have seriously harmed the country’s ability to access food, medicine, energy supplies, and components needed for industry. They have hampered North Korea’s economic development by impeding trade and foreign investment. The U.S.-led sanctions have failed to achieve the senders’ intended goal of regime or policy change, and instead have made it very difficult for North Korean people to obtain the basic necessities of life.

Koreans in both North and South want peace and reconciliation. South Korean President Kim Dae Jung introduced a Sunshine Policy towards North Korea from 1998 to 2007. A historic summit meeting in 2000 between Kim Dae Jung and Kim Jong Il represented a thawing of tensions, and paved the way for joint economic and humanitarian initiatives. After decades when people did not know if their relations were alive or dead, the governments allowed brief reunions between family members separated since the war. 128,000 South Koreans registered as part of this program. Just over half of them (56 percent) were still alive in 2014, and more than 80 percent of these survivors were over 70, according to South Korea’s Unification Ministry, which handles inter-Korean relations. Family reunions are a highly emotional issue, considered to be a barometer of relations between the two Koreas. Also under the Sunshine Policy, a joint economic initiative, the Kaesong industrial park, ten kilometers (six miles) north of the DMZ, was opened in 2004. By April 2013, 123 South Korean companies employed approximately 53,000 North Korean workers and 800 South Korean staff at Kaesong. The companies can pay lower wages than in South Korea while employing educated people who are fluent in Korean. Moreover this arrangement provides North Korea with an important source of foreign currency. These humanitarian and economic initiatives are affected by the ongoing volatile situation and fluctuating tensions between the two governments. During 2013, for example, Kaesong was closed for five months when tensions rose over North Korea’s third nuclear test followed by the annual military exercises between South Korea and the United States. A peace treaty is an essential first step toward ending the unresolved Korean War and normalizing relations between all parties involved. Normalized relations are central to building peace, friendship, and cooperation on the Korean peninsula and in Northeast Asia.

Crossing Borders: a feminist history of Women Cross DMZ

by Suzy Kim